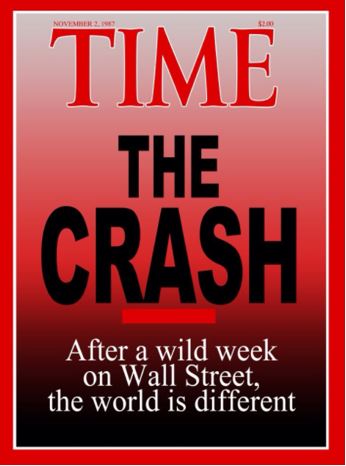

Thirty years ago this week, the stock market had been very strong since the start of the year and investors vacillated between greed and anxiety. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) peaked with a 43% gain by August that year, and had retreated by more than 16% from its peak. Then on October 19, 1987 the DJIA plunged nearly 23% on that one day for the single most horrendous panic-induced selling in Wall Street history, commonly referred to as Black Monday.

What caused the drop? In the prior five years, stocks were up 229% on average while the cumulative earnings per share had grown just 17%, so valuations (price to earnings ratios) had expanded hurriedly. Investors were jittery about high interest rates potentially choking off much-rumored acquisitions and general economic growth. Worries were building that stock gains could not be sustained through year end. Washington floated the idea of a new, higher tax proposal and investors hated it. On Friday of the prior week, stock prices were dropping.

When the markets opened that Monday, sell orders were too numerous for existing systems to function properly and program trading ensued, dumping more and more stocks as they declined. New and complex hedging strategies utilizing derivatives had been introduced in the 80’s, adding to the toxic avalanche. Financial regulators didn’t know how to deal with the situation.

State-of-the-art Quotron machines that reported the price and volume of each stock’s trading via phone lines onto paper at brokerage offices across the country were running sorely late–about 45 minutes behind each trade. Thus an order to sell a stock at the market price was a shot in the dark. Confirmations could not keep up with the trades either, so most didn’t know how their trade was executed until days later. In current terms, a fall of the same magnitude would knock the DJIA down by more than 5,000 points from its current level of 23,000.

I remember that day well, in my broker’s office writing a check for a stock purchase that occurred the prior Thursday, and there was nothing a rational person could do but cut the check. Mike Binger had started his career just a few months earlier. Louis Rukeyser on the popular PBS show Wall Street Week told us, “It’s just money. The people who loved you last week still love you.”

The stock market recovered dramatically the following day, and finished up for the full year. It would be another two years before the DJIA reached its August, 1987 high. Importantly, the panic did not affect the economy or corporate earnings; no recession followed the crash.

Could the same thing happen again? This is a question that has been posed ever since that fateful day.

First of all, financial regulators have expanded oversight and controls, stepping in to stabilize markets in some situations. They have instituted “circuit-breaker” rules which require a stock or the overall market to stop trading temporarily when systems become overloaded with sell trade requests, restoring order.

Secondly, today’s technology has been proven to handle volume that is many times the size of volumes just a few years ago. Trades are made and confirmed in nano-seconds to at-home investors, not just institutional investors, making the process very efficient.

Other sudden one-day declines have occurred since 1987 in stocks as well as other asset classes, although minor by comparison and with little follow-through after the initial decline. Program trading has expanded dramatically, but most quantitative investors have factored liquidity, leverage and investment time horizons into their various metrics.

Much has been learned and a wide variety of economic, corporate and trading data is now at our fingertips. Active money managers can still be counted on to purchase bargains as stocks sell off.

To expand on these Market Reflections or to discuss any of our investment portfolios, please do not hesitate to reach out to us at 775-674-2222.